JMAP 2022 - A First Time for Everything

An Impoverished View.

Busy first clinic at Hiteen/Schneller.

Explored the camp afterwards.

Jerash/Gaza camp is apparently more destitute.

I’ll be there tomorrow.

What a day!

I don’t often find myself speechless but today was an exception. I woke up at 6am after five-and-a-half hours of mediocre quality sleep. Perhaps I was nervous. Or excited. Or apprehensive. Not sure. One thing was for certain - I was raring to go and the small matter of sleep deprivation was filed haphazardly to one side. A quick breakfast consisting of eggs and fül medamas (a traditional Middle Eastern dish consisting of cooked fava beans with a drizzle of olive oil and various herbs and spices) was followed by unintentionally putting my contact lenses into the wrong eyes. Looking into my rear view mirror, about to switch on the ignition, I utter to myself “why do my eyes feel so bloody tired!”… quickly realising the error of my ways. It just so happened I packed an extra pair of contact lenses in my bag - problem swiftly solved.

As I swept through the outskirts of Amman, heading east, there was a palpable decline in the quality of the housing, roads and general infrastructure - as though I was acclimatising for what I was to witness later. After several detours, I made it to the outer edge of the Hiteen/Schneller refugee camp and parked opposite the Jordan Medical Aid for Palestinians (JMAP) clinic. I had no sooner locked my car door (correctly on this occasion) and my acclimatisation period was complete; I was almost immediately approached by a little girl, probably no older than 8 years old: “Ammo! Ammo!” (translates to “Uncle! Uncle!” in English) she called out - knowing that despite my Middle Eastern looks, I had the foreign ‘veneer’ of a freshly ironed shirt, clean trousers and an authentic watch - before asking if I had just one Jordanian Dinar (about £1.20) so she could buy breakfast for her siblings. Regrettably I had left my cash at home but I was able to negotiate with the local bakery to accept a contactless card payment for two-dinars worth of freshly baked bread for the little girl to take home.

Hiteen/Schneller Clinic.

Situated at the edge of the refugee camp.

7:30am - I’m barely awake.

Walking into the unknown.

There’s a first time for everything.

I was warmly greeted by the clinic co-ordinator who immediately offered me coffee. In fact I was offered coffee about 20 times throughout the course of the day - each time I politely declined. I’m not a big coffee drinker. In hindsight I could have done with a cup or three! The clinic co-ordinator was interested in my academic and professional background. She herself has rheumatoid arthritis and did not wait long before informally seeking my professional advice. This is the done thing here. Whether it’s family, friends, friend-of-a-friend or a stranger, once it is known you are a doctor - particularly a British-trained doctor - there’s no escaping the armchair consultation. My fall from grace with our dear clinic co-ordinator couldn’t have been more amusing. You see, when asked how many patients I might be able to review during my 8am til 5pm schedule today, I naively suggested the equivalent of two fairly standard NHS clinic templates - about 20 patients. Her lips started quivering - I knew she was about to laugh. “Is that too many? Too little? How many do the doctors normally review here?” I rushed to ask. “50-60-70 per day” she casually responded. We arrived at a compromise - 40 patients. The JMAP general practitioner, internist and orthopaedic consultant had been informed of my arrival therefore countless referrals had already been made to me, not to mention ‘walk-in’ patients with rheumatic ailments. This was going to be an uphill struggle.

Pleasant Clinic Space.

A chair for the incredible nurse who kept me on track.

Almost everything is paper-based.

Except for viewing x-rays.

I was quickly introduced to the clinic manager, Yaseen - a delightfully friendly guy, and Sister Rahaf - arguably the star of the show. Sister Rahaf was my assigned clinic nurse and she was an inspiration. Sister Rahaf had an extraordinary ability to develop rapport with patients within milliseconds it seemed. “Mama”, “Baba” (affectionate Arabic terms for mother and father) she would respectfully address the patients, and immediately they were at ease. She had a sixth sense. As I was about to begin my lengthy rampage of logistical questions regarding the clinic (my former colleagues will know I am a stickler for detail), she knew it was time to ruthlessly chuck me into the deep end. Bag down, head up, and to my surprise the first patient was already sitting on the opposite side of the desk. Ready or not, the show was on the road.

Examination/Procedure Area.

Adjacent to my desk.

Ample room for examining patients.

Privacy and dignity always a priority here.

I ran out of injectable steroids.

My Arabic is decent but certainly not as good as my English. Although I’ve never lived in an Arabic speaking country, I am fortunate enough to have parents who valued the worth of being bilingual so I learned the language at home while growing up. However, medical consultations in Arabic are something new to me. There were the occasional Arabic speaking patients in the UK who would benefit from my Arabic language skills, yet to conduct an entire clinic in Arabic with rheumatology jargon - consultation after consultation - without taking refuge in English was a relentless undertaking. I think the patients were rather endeared by my ability to discuss the finer details of autoimmune disease in Arabic (something I admittedly had to coach myself prior to this trip) whilst coming unstuck with the Arabic translation of the word “gout”. Sister Rahaf - the saviour - came to my rescue!

Sister Rahaf also had an effective way of cajoling me to speed up my consultations. By the time it was 10:00am I had reviewed just 5 patients; at this rate I was on track for a midnight finish if all 40 clinic slots were filled. Sister Rahaf stepped outside for a brief moment and came back with a wad of notes she had acquired from the main reception: “That’s it, almost all your slots have already been filled and they’re all sitting patiently in the waiting room for you” she exclaimed. I knew this was my cue to get my act together. My history taking sharpened up and my examinations were more targeted. By the end of the day I had reviewed between 30 and 35 patients; I lost count of the exact number. To think that the other doctors at JMAP go through lists of 60 or 70 patients in a day, while delivering a high quality of care, is mightily impressive.

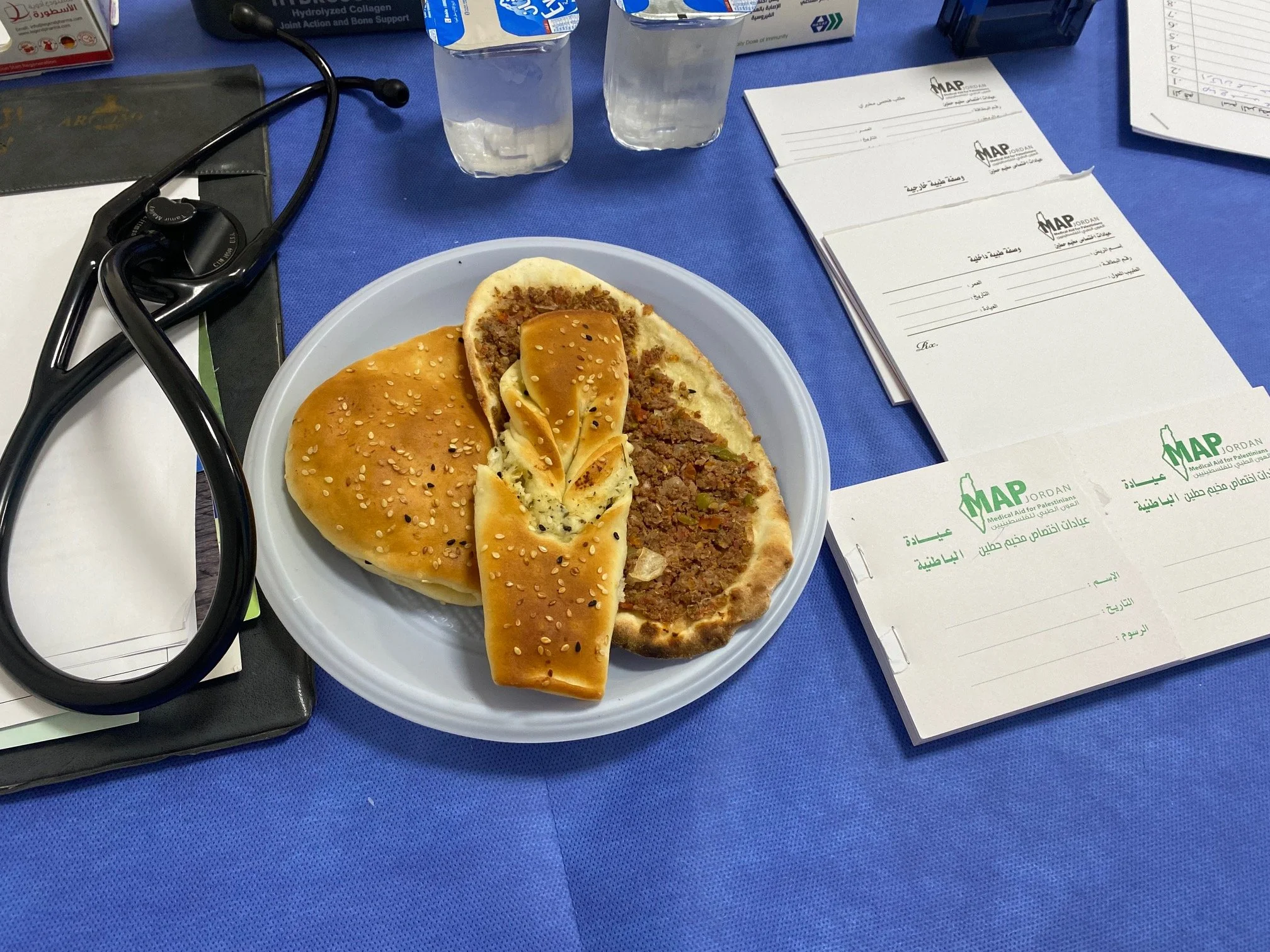

A Brief Respite.

After the first 5 hours of back-to-back consultations.

Lunch brought to me.

A delightful surprise.

A moment to pause and reflect.

I want to briefly conclude by reflecting on two situations from today - an interesting case and an interesting observation.

The interesting case: I was asked to review an 11-year-old girl with a genetic condition called Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF), typically first occurring in childhood, which presents with short-lived episodes of recurrent fever alongside abdominal, chest and joint pain. FMF usually occurs in individuals of Mediterranean and Middle Eastern descent. Symptoms can be incredibly painful and debilitating for those affected, sometimes resistant to standard treatments, with the potential for severe organ-threatening complications. Sister Rahaf mentioned earlier in the day that there was a cohort of patients in the region with this disease. The mother had heard of my arrival and arranged to bring her young girl to my clinic. She had been struggling with almost daily fevers and a concerning amount of weight loss over the last two months, despite exhausting standard treatments. Fortunately I had an incredibly informative six-month rotation during my training with the Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology team at the Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre in Oxford where I saw two or three challenging cases of FMF requiring escalation to biologic treatment - drugs which target very specific parts of the immune system, specifically blocking an inflammatory protein called interleukin-1. A phone call to the JMAP consultant paediatrician quickly led to a referral to a specialist Paediatric unit in central Amman where - with financial support, I hope - this young girl will receive the treatment she so desperately needs.

The interesting observation: There is sometimes an expectation amongst patients in developing nations that all symptoms and conditions need to be treated with medications. I somewhat understand why this heath belief exists. Much like the various patients today who told me they tried a combination of topically applied honey and olive oil to treat their inflammatory arthritis. Before embarking on this medical mission, I promised myself I would not resort to the dishing out of shotgun prescriptions if I didn’t truly believe they were necessary. My efforts to explain the non-pharmacological treatments of fibromyalgia or osteoarthritis were almost always met with scepticism by patients today, perhaps fuelled by the sense of feeling short-changed by a British-trained consultant whom they expected would have a drug-based solution to their every symptom. Or perhaps they felt like they were receiving second-class care due to their demographic circumstances. I quickly realised that if I reassured them that the explanation, advice and treatment (despite being non-pharmacological) they were receiving from me was similar to what I would advise my patients in the UK, their scepticism would melt away. Their guard would fall, their trust would bloom and a pleasing receptiveness to my suggestions would ensue.

Tomorrow I make my way to the the most impoverished of the three refugee camps - Jerash/Gaza. My eye-opening experience is certain to continue.